The Backstory

How does a boy raised in the Deep South who became a professor of religious studies come to write a book about his 20 year journey with LSD?

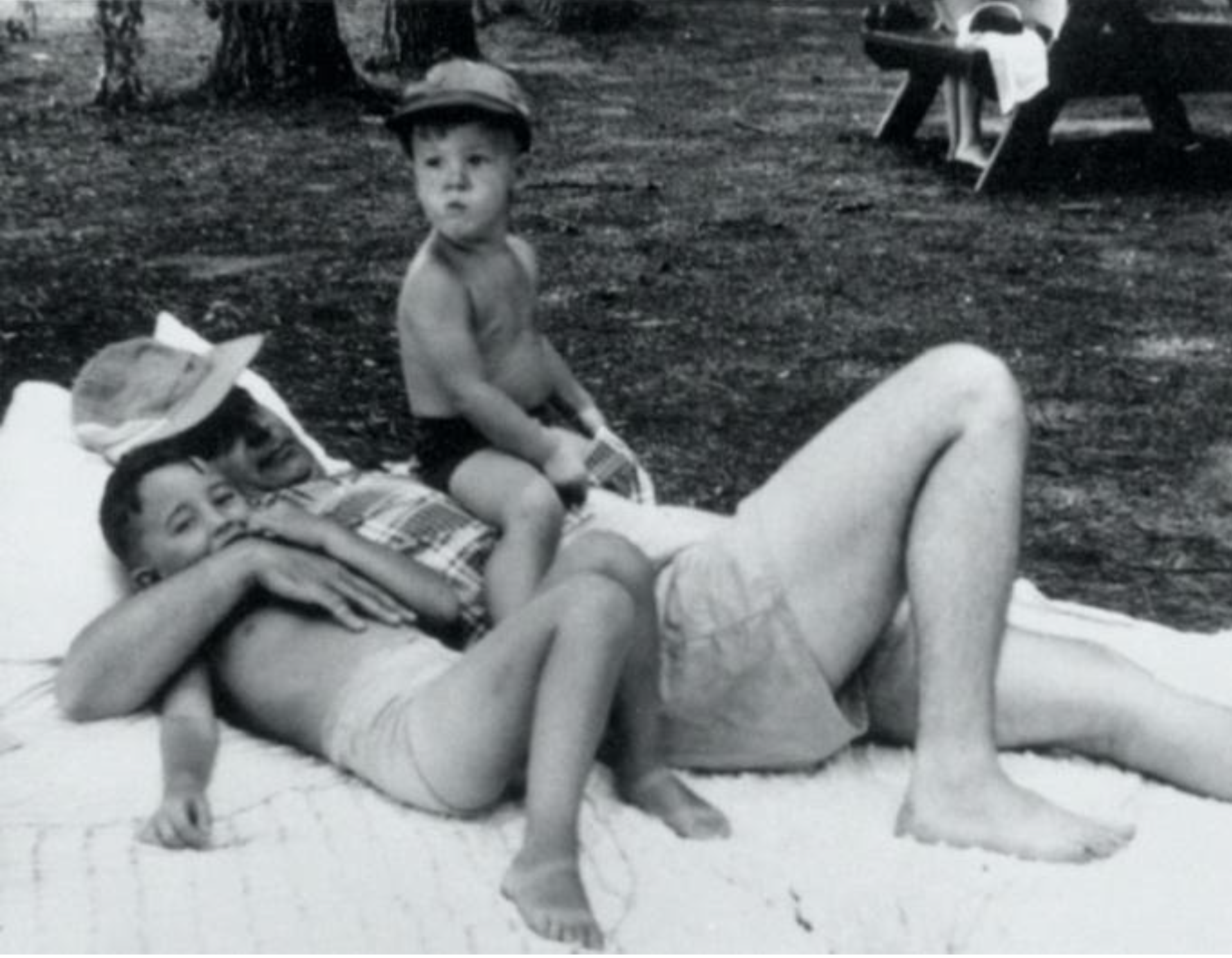

I was born in 1949 in Vicksburg, Mississippi, a small town steeped in its Civil War history and home of the largest Corps of Engineers research laboratory in the United States, the Waterways Experiment Station, where my father was a senior administrator. This is what brought my family to Vicksburg. I enjoyed growing up in the South, with its strong family traditions and outdoor adventures. My dad taught me to hunt and fish, as Southern gentlemen do, and I learned to camp and ride horses at the Troop 7 Boy Scout camp outside of town, free of the scandals that plagued scouting later.

My family was Roman Catholic, in an observant but open-minded way. From as early as I can remember, I wanted to be a priest. Where did this draw to the spiritual life come from? It felt like something I was simply born with. I entered the seminary in high school, at a time when this was still done, but after four years decided I was not cut out for celibacy and left. Overall, my Catholic upbringing was good to me. It introduced me to men and women of integrity, protected me from the racism that surrounded me, and connected me to a tradition with deep intellectual roots.

Chris’ brother, father and him.

I went to the University of Notre Dame where I got into an honors program that freed me from the usual prerequisites and let me pick my courses from across the undergraduate and graduate curriculum. I studied widely, eventually majoring in religious studies, technically “theology,” with a focus on New Testament studies, learning Greek and Hebrew in the process. I also read Carl Jung and Mahatma Gandhi, who made a deep impression on me. Against the backdrop of Vietnam, I gave up my guns and became a conscientious objector. By the time I graduated from college, I had left Catholicism, a strange outcome for someone who had just been given the theology department’s award for excellence.

As I continued my studies at Cambridge University, my passion became the search for the historical Jesus, a scholarly movement to extract the original teachings of Jesus from the many layers that had accumulated around it in scripture. There I learned the art of peeling away history with form criticism, redaction criticism, and textual criticism. Ironically, the historical Jesus became my way out of Christianity, for in him I found a depth of spiritual realization that was larger than Christianity. And I continued to read Jung.

When I came to Brown University, I realized that I had gotten what I wanted from Biblical Studies, so despite being halfway toward my doctorate, I changed horses and began again. At Brown I studied the broad contours of Western religious thought, following Christian and Jewish theology through the great minds of the middle ages into the fateful encounter with the Age of Enlightenment. I absorbed the philosophical revolutions of the modern mind, fell in love with science, and watched it demolish theology with the sheer grandeur of the universe it was discovering.

Eventually I fashioned myself into a philosopher of religion in the analytic tradition of linguistic analysis. After 300 pages of technical analysis, my dissertation concluded that using language derived from finite existence to describe an infinite God was like shining flashlights at the stars. Our words may launch well but they fizzle out semantically before they reach their destination. I finished seven years of graduate school as a deeply convinced agnostic with a strong atheistic bent. This is the mind I brought to my psychedelic studies – well trained in the history of religious thought, skilled in analytic discourse, and swept clean by the modern era.

In 1978 I began my academic career in the department of Philosophy and Religious Studies at Youngstown State University, where I would teach for 33 years. Just as I was making this pivot, I met the work of two thinkers who would change the course of my life – Ian Stevenson of the University of Virginia and Stanislav Grof. Ian Stevenson’s book Twenty Cases Suggestive of Reincarnation stopped me in my tracks. His impeccable scholarship on children from around the world who have spontaneous memories of their previous lives persuaded me that reincarnation was a basic fact of life. Here was empirical evidence that the reductive materialism that had become intertwined with science was simply false, for it demonstrated that mind does not reduce to brain and that there must be some dimension outside physical reality where consciousness exists intact in-between our incarnations. Stevenson’s research forced me to erase my intellectual blackboard and rethink human existence from scratch. My first book, Lifecycles (1990), was my response to Stevenson and my first attempt to think through the ramifications of living in a reincarnating universe.

Stanislav Grof was to have an even larger impact on my life. At the time, Grof was the foremost authority on integrating psychedelics into psychotherapy. His compelling presentation in Realms of the Unconscious convinced me that LSD could be used safely in carefully structured settings to engage the deep psyche with positive therapeutic outcomes. I quickly saw that his work represented a turning point not only in psychology but in philosophy of religion as well. Here was a powerful method, born in a modern laboratory, that allowed one to explore the deep structure of consciousness and experientially probe questions that philosophers have pondered for centuries. I simply had to see what LSD might teach me about myself and the universe. I was 30 years old and about to begin the work that would define the rest of my life.

I knew that this project would require a sustained inquiry lasting many years. At YSU I had a stable setting that would allow me to pursue this work, if I kept it secret. So I settled into the rhythms of teaching at an open-enrollment, undergraduate university while in my private life I began what would become a 20 year psychedelic self-experiment using Grof’s protocols.

I love teaching. I love the classroom dance. At YSU I was fortunate to be able to design a series of courses that served my students while simultaneously supporting my psychedelic inquiry. Early on I was asked to teach a course on Eastern religions, and this began a lifelong study of Eastern thought, rounding out my earlier Western focus. Buddhism’s agnosticism appealed to me, as did its practical methods for realizing spiritual awakening. I also taught courses on world religions – adopting Huston Smith’s perennialist approach – psychology of religion, comparative mysticism, Buddhism, and a course I called Transpersonal Studies, which explored research on reincarnation, near-death experiences, and out-of-body experiences. Periodically I taught seminars on the new paradigm emerging in science and consciousness studies. Taken as a whole, these courses allowed me to gather the intellectual background that helped me make sense of the experiences that were emerging in my psychedelic practice. They also helped me recognize when my experiences were taking me beyond these maps and breaking new ground.

For many years I was not able to share my psychedelic work with my department or my students because of LSD’s illegal status, and my contact with the national psychedelic community was limited to reading their books. For close to twenty years I worked largely in isolation, which had its pluses and minuses. This began to change when I wrote Dark Night, Early Dawn (2000), where I began to share some of my psychedelic experiences and unpack their philosophical implications. This manuscript brought me to the California Institute of Integral Studies where I became adjunct faculty in the Department of Philosophy, Cosmology, and Consciousness, teaching graduate students eager for the psychedelic conversation, many of whom were psychedelically initiated themselves. This led to a two year appointment as the Director of Transformative Learning at the Institute of Noetic Sciences in 2000-2002, where I made many friends in the nonprofit world and consciousness community before returning to Ohio.

Chris at IONS.

Though I ended my psychedelic sessions in 1999, it would take many years for me to fully internalize my journey. In 2008 I published The Living Classroom where, without mentioning psychedelics, I described how my private “spiritual practice” had begun to impact my students at the university, demonstrating that states of consciousness are contagious. I also described the collective learning fields that grew around my courses over the years and shared the pedagogical strategies I had developed for working with them. In 2011 I retired from YSU and in 2019 published LSD and the Mind of the Universe where I finally told the complete story of my psychedelic journey. After twenty years of sessions and twenty years of reflection and integration, it was time.

You can read my history as a story of gradual unfolding, with one decision leading to another until the sum is totaled, but there is another way of reading it. When I look back over my life, it feels like my psychedelic work was so central to this incarnation that everything in my life was calibrated to bring it into being. Much like James Hillman describes in his book The Soul’s Code, it was a destiny discovered.

Alongside the story I’ve shared here is an equally important story of family. While at Brown I met and married Carol Fitzpatrick, who was an undergraduate on her way to becoming a clinical psychologist with a practice in contemplative psychotherapy. We were married for 24 years and had three wonderful children together. We separated in 2000, Carol moving to Santa Fe and I to California. When I returned to Ohio in 2002, Christina Hardy, whom I had met at CIIS, came with me. Thus began the second great partnership of my life. After a successful career as the director of Career and Academic Advising at YSU, Christina now pursues her deeper calling as an astrological counselor and past life therapist in Weaverville, NC, where we now live.

Christina and Chris.

︎